Local and organic produce for sale at Columbia’s Rosewood Market (Photo by Lauren Larsen/Carolina News and Reporter)

Weeks after South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster rejected federal funds to provide summer food stipends for low-income children, legislators are urging the governor to reverse course – although that seems unlikely.

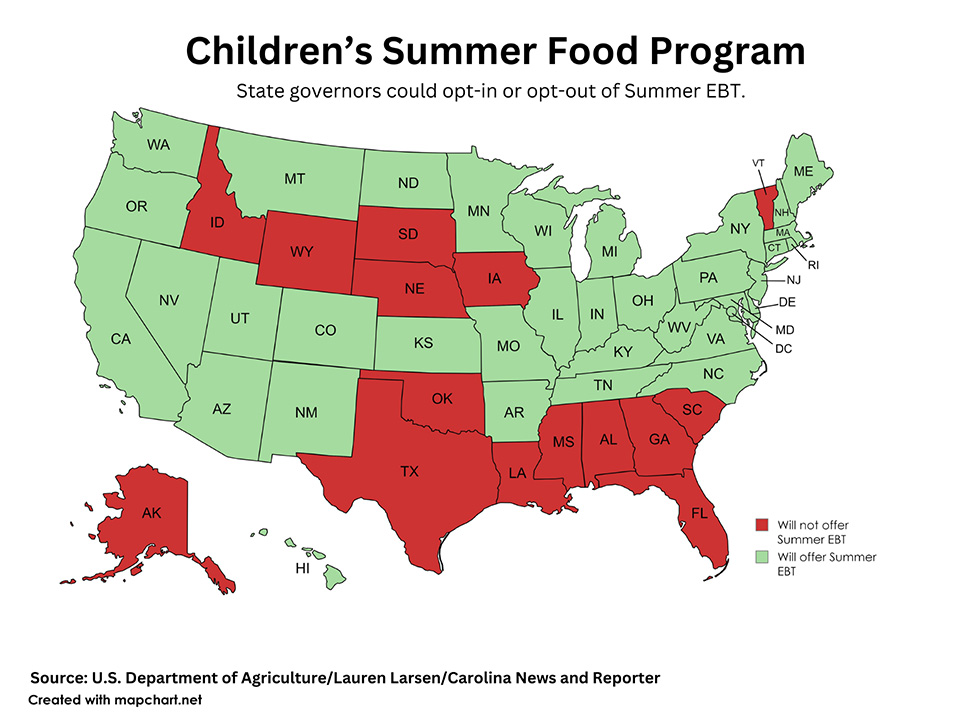

The Biden administration signed a bill to give low-income children $40 per child per month, totaling $120 over the summer for food if states said they were interested. But McMaster was one of 15 Republican governors who failed to inform the federal government his state wanted to participate in the new program.

Now, some state legislators are asking the federal government for more time for South Carolina to change course. Still, they’re pessimistic that McMaster will change his mind.

“This was a way to try to build that bridge to keep kids nourished and fed,” said Juliana Palyok, executive director of the South Carolina chapter of the National Association of Social Workers. “Without the assurance of that, there’ll be so many people that may go hungry. And that is hard to even imagine.”

McMaster has said South Carolina already has programs to feed children in need, along with food banks to help fill the gap for their families. He also said the funding that’s coming from the federal government feels like an ongoing pandemic handout even though states would have to pay some administration costs.

Summer EBT will give low-income families electronic benefit transfer cards that can be used at grocery stores.

States interested in participating had to send a letter of intent to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Services by Jan. 1.

Some S.C. Democrats and representatives of nonprofits that help feed children said McMaster should have sent a letter of intent, even if there were some questions unanswered.

“To take our tax dollars and to make sure that it goes to feed every hungry kid in America, except South Carolina’s, is absurd,” said Sen. Mike Fanning, D-Fairfield.

The partisan split

Fanning said the federal government would cover a major portion of the program’s cost but the state would have a role in paying to administer the new program.

“We know that we will have to be spending something, and keep in mind that we already have programs to provide food for people below a certain income,” McMaster said in a press conference in late January. “Also keep in mind we have food banks galore all over the state.”

McMaster spokesman Brandon Charochak said there’s no way to estimate the cost until the U.S. Department of Agriculture finalizes its guidance.

Fanning said some estimates put the state’s potential annual cost at around $3 million.

“Three million is a very small amount to ensure that our children are getting additional resources to eat nutritious food in the summers,” said Brenda Shaw, the chief development officer at Lowcountry Food Bank.

In contrast, Rep. RJ May III, R-Lexington, stressed the importance of creating more work opportunities rather than government assisted programs.

“At the end of the day, no amount of government assistance provides a quality of life like a good, high paying job,” May said.

Other Republicans said it wasn’t their decision to accept or reject the funds, or that they didn’t have enough details.

An identical resolution was filed Jan. 24 in both houses of the South Carolina legislature asking Congress to extend or eliminate the opt-in deadline. But the bill remains in respective Senate and House committees as of the time of this publication.

“Because the Republicans control the House and the Senate, I think it was probably unlikely something like this would get passed,” said Sen. Tameika Isaac Devine, D-Richland.

But some lawmakers feel strongly about the program.

Days after the resolution was filed, some Democratic legislators from South Carolina flew to Washington to discuss workaround options that would allow the state to participate.

Sen. Deon Tedder, D-Charleston, was among them. He said the USDA told them it wouldn’t turn away any state if the governor decides to send in a late letter of intent.

A continuing need

Last year, before it expired, all states had access to a pandemic-related EBT benefit created because children were staying home and didn’t have access to school food programs.

“At some point, we must end these pandemic programs,” McMaster said. “The pandemic is over. And this is how the government gets bigger and bigger – bigger democracies, bigger entitlements.”

Jennifer Augustine, associate professor of sociology at the University of South Carolina, said families have grown accustomed to receiving the benefit because of growing inflation around food prices.

“Families are kind of facing a double whammy,” Augustine said. “They’re losing benefits they had previously, and they’re facing additional costs.”

Without the pandemic program, about 500,430 children will be affected in South Carolina this summer, said Erica Cheeks, equitable access advocate at Harvest Hope Food Bank, which serves almost half of the state’s counties.

Without Summer EBT, children and families still will have access to food share programs administered through the Department of Agriculture and Education, churches and nonprofit food banks – but these programs come with challenges. Access challenges can include knowledge, accessibility and transportation to feeding sites as well as an area’s food availability.

The Lowcountry Food Bank goes into the year with a projected budget based on food insecurity numbers and what was raised in the past, but the increase in food demand in the summer presents hardships, said Chief Development Officer Brenda Shaw.

Harvest Hope’s Cheeks said the summer months are typically when the organization sees its lowest donations and volunteers. Harvest Hope last summer received about 400,000 fewer pounds of food than during the fall quarter. Harvest Hope averages around 1,700 volunteers in the fall months but less than 1,500 in the summer months.

Fanning said because Democrats and Republicans agreed on the bill in Congress, it was never meant to be a partisan issue.

“It saddens me to see that some folks now, after Republicans and Democrats have actually agreed on something, are now wanting to poke a sleeping bear and to make something partisan out of it,” Fanning said.

Child poverty in South Carolina is around 19% of the population, much higher than in most states, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Children living in poverty without access to food can face emotional and physical setbacks, USC’s Augustine said.

“Food insecurity is an enormous issue,” she said. “It is consequential to children’s emotional development. And during the school year, it’s consequential to their cognitive development.”

Some legislators intend to keep pushing for Summer EBT in South Carolina for future summers.

“For purposes of next summer, 2025, I know for sure we’re going to continue to push this,” Tedder said.

Fresh bananas, oranges, lemons and onions at Rosewood Market (Photo by Lauren Larsen/Carolina News and Reporter)

Fresh Autumn Glory apples at Rosewood Market (Photo by Lauren Larsen/Carolina News and Reporter)

A volunteer sorts cans at Harvest Hope Food Bank in Columbia. (Photo courtesy of Harvest Hope/Carolina News and Reporter)